By Clara Tonecker

Introduction

Governments, militaries and entire economies are completely dependent on the availability of information. Transportation systems, industrial supply chains, emergency response capabilities and communication systems are only examples of the vast array of sectors that rely on the internet (Miani, 2020). While the internet is perceived as ‘intangible’ or wireless, it is often forgotten that it depends on core physical infrastructure, part of which are fiber optic submarine cables (Winseck, 2017). The earth is covered in 1.3 million kilometres of submarine cables that carry trillions of terabits of data at light speed. However, these cables are subject to numerous threats, ranging from ship anchoring and fishing to sabotage, espionage and warfare (Pandey & Bhushan, 2023, 9). This article is meant to give an overview of a variety of topics relating to submarine cables, but it simply covers too much ground to handle a particular topic in-depth. The article will explain the significance of fiber optic submarine cables, provide a short historical background and then answer the following security-related questions:

- What kind of threats are these cables facing?

- What geostrategic significance do these cables hold?

- Which protection measures can be implemented to improve cable security?

Significance and national security implications of submarine cables

Fiber optic submarine cables are the backbone of the modern society, transmitting 99% of global data traffic. From an economic perspective, these cables are crucial for the efficiency of global supply chains, international commerce and maintaining economic stability. They enable the transmission of financial data including banking transactions, stock market information and secure communications between businesses (Pandey & Bhushan, 2023). $10 trillion of financial transfers are carried by submarine cables every day (Wall & Morcos, 2021). Furthermore, they are vital for international telecommunication networks, enabling real-time communication ranging from text to voice and video messages between individuals, businesses and governments. They enable access to online services such as websites, social media platforms and media content from live broadcasts, TV shows, streaming services and music platforms. From an academic perspective, they transmit scientific data and ensure access to educational resources and research across continents. Marine-based energy projects such as offshore wind farms and submarine oil and gas pipelines are dependent on the transmission of control signals and other vital data (Pandey & Bhushan, 2023).

Lastly, their functionality has a significant impact on national security and defence. They ensure secure communications between government representatives and bodies, intelligence agencies, and military units. This data is heavily encrypted to prevent espionage and manipulation. For military units, real-time communication and data sharing improves coordination, situational awareness and fast response. Moreover, sharing critical intelligence between governments contributes to the fight against transnational crime such as human trafficking, drug trafficking and terrorism. They also contribute to disaster resilience, ensuring the coordination of emergency response units and providing alternative communication routes when terrestrial infrastructure has been damaged. Therefore, the security of fiber optic submarine cables is vital for the safety and security of the human population (Pandey & Bhushan, 2023).

A short historical background

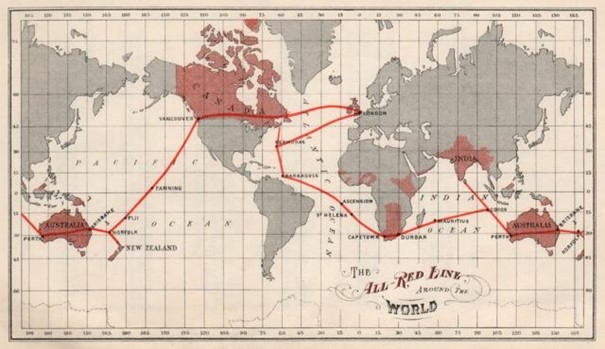

Modern global communication was shaped in the second half of the 19th century. After three failed attempts, the first transatlantic cable was successfully laid in 1866. The Anglo-American Telegraph Company recovered the costs of laying the submarine cable within two years, resulting in an upsurge of submarine cable systems across the North Atlantic. In the following years, major world cities were connected to the cable system such as Bombay in 1870, Hong Kong in 1872, Shanghai in 1873, and Buenos Aires in 1874. Even back then, communications technologies were perceived and used as ‘weapons of politics’ or ‘tools of the empire’ (Winseck, 2017). The strategic value of these cables was quickly understood by the British Empire, the era’s dominant power, which swiftly decided to link all British colonies. All landing stations to which the cables were connected had to be on British soil and staffed by British workers. This submarine cable network became known as the “All-Red-Line” (see Figure 1) (Burnett & Berdan, 2024).

Figure 1

Route of the “All-Red-Line”

Note. From ”To Secure Undersea Cables, Take Lessons from the British Empire’s All-Red Line“, by D. R. Burnett & K. Berdan, 2024, Proceedings, 150(7) (https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2024/july/secure-undersea-cables-take-lessons-british-empires-all-red-line). In the public domain.

The geography of these submarine cables has remained similar, as many of the same ‘world cities’ are linked and routes laid in the 19th century are still dominant routes now. The copper cables supporting telegraphy and telephony have all been decommissioned and replaced by fiber optic cables (Winseck, 2017). More than 400 active cables worldwide, covering 1.3 million kilometres, ensure critical connections, international data transmission and internet connectivity (9). They are between 1-20cm thick, largely consisting of multiple layers of ‘armour’ and an outer membrane that prevents the intrusion of plants, animals and seawater. The actual data is transmitted only on a hair-thin fiber. These cables connect two landing points located on two different shores, which supply power to the cable (Sherman, 2021). A regularly updated map of submarine cables can be viewed here.

Threats – cable cuts, espionage, cyber attacks

The submarine cable network faces a multitude of threats. The most common threat is accidental or natural physical damage deriving from commercial fishing, shipping or underwater earthquakes, amounting to 150 to 200 cable faults annually (Wall & Morcos, 2021). For instance, in 2008, the submarine cables SEA-ME-WE 3, I-ME-WE and TE-North were cut, which was later attributed to dragging ship anchors off the coast of Egypt (Pandey & Bhushan, 2023; Saffo, 2013). This led to 14 countries losing internet connectivity, affecting 75 million people (Saffo, 2013; Sherman, 2021). For instance, the Maldives were completely cut off. Moreover, Egypt is one of the most concentrated cable landing points globally because almost all the cables linking Europe, the Middle East and Asia go through the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. This makes Egypt a valuable and vulnerable location for the global internet infrastructure as well as a potential target for a terrorist attack. In 2013, three divers were arrested by the Egyptian coastguard as they were caught trying to cut the SEA-WE-ME 4 cable near the coast of Alexandria (Saffo, 2013). Historically, state-sponsored sabotage of submarine cables has played a role in many armed conflicts. As early as 1872, a war between Chile, Peru and Bolivia resulted in the subsea telegraph line between Lima and San Francisco being cut (Burnett & Berdan, 2024). On August 5, 1914, only a day after Britain declared war on Germany, almost all of Germany’s submarine cables were cut, making it a prime example of strategic information warfare (Corera, 2017a).

However, cable cuts are not the only threat. These cables carry sensitive information, ranging from military communications to diplomatic correspondence. Therefore, tapping into them presents an attractive spying opportunity. The first espionage attempts date back to the late 19th and early 20th century. For instance, the small British town Porthcurno became an international hub of telegraph cables, where British intelligence used its access to eavesdrop, essentially taking advantage of the British Empire dominating the international telegraph system (Sherman, 2021; Corera, 2017a). By the beginning of the First World War, a global system of interception had been established, positioning men who were called ‘censors’ in many cities, among those being not only Porthcurno but also Hong Kong, Malta, Singapore, Cape Town and Cairo. The probably most famous message that was intercepted during the First World War was the Zimmermann Telegram, which significantly altered the course of the war (Corera, 2017a). British intelligence officers decoded a message between German foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann and the German ambassador in Washington. It revealed that should Mexico join a war against the US, Germany would offer the territories of Arizona, Texas and New Mexico in return. This incentivized the US to join the war and broke the stalemate (Corera, 2017b). Another historic example of submarine cable espionage took place during the Cold War in the 1970s. The US National Security Agency conducted a covert operation, attaching recording devices to a cable off Russia’s Eastern coast using submarines and divers, which consequently enabled it to listen in on Russian military communications (Sherman, 2021).

Furthermore, the submarine cable network is vulnerable to cyber-attacks. A hacker could gain control of a network management system, which manages all the data that is transmitted by the cables. This can disrupt or divert data flows or delete the wavelengths used to transfer the data, also called a ‘kill click’ (Wall & Morcos, 2021). A major problem is that more and more companies that manage cable infrastructure are using a remotely controllable software, creating another layer of control that can be attacked. Adding to the risk, the cybersecurity requirements of many governments for these companies are relatively low. In 2022, a telecommunications company’s system in Hawaii was breached by hackers who acquired the credentials to disrupt communications completely, but the attack was stopped by the Department for Homeland Security (Sherman, 2023).

The geostrategy of submarine cables

The geostrategic significance of submarine cables cannot be denied. In historical conflicts, it has been a common method of states to deny access to critical infrastructure or critical resources to adversaries. If a country gains influence over a submarine cable line or network, it has access to the backbone of the world economy. As described above, disruptions can have a severe impact on all aspects of life, most importantly, national security (Wall & Morcos, 2021). Submarine cables are largely owned by private companies, with some being state-controlled or intergovernmental. These companies have a major influence on the shape and security of the global internet (Sherman, 2021). While a single cable is often financed by multiple countries, usually one company from one of those countries is contracted to lay it. Additionally, the landing stations are managed by different organizations from different countries as well, creating a large network of actors that are involved in the construction, maintenance and repair process which can subsequently exert influence (Sherman, 2023).

In the cases of China and Russia, this can be perceived as a security threat. For example, Chinese state-owned telecommunications companies such as China Mobile, China Telecom and China Unicom have massively increased their investments in submarine cables. For about two thirds of these cables, at least one landing station is located in China. The control of a landing station allows an actor to better monitor the data traffic that is transmitted through the cable. Moreover, a cable investor can exert influence over the cable route and which places it connects. In 2020, the Pacific Light Cable Network, a submarine cable project involving Google, Facebook, a US-based company and a Chinese-owned company, was blocked by the US government due to concerns of Chinese espionage (Sherman, 2023). On top of that, a large number of cables run through the South China Sea to which China has access. Consequently, US and Australia are planning to lay a new cable route passing South of New Guinea that connects the US with Australia, Indonesia and Singapore, attempting to reduce the risk of Chinese sabotage or espionage (Miani, 2020). Another threat of Chinese influence lies in Chinese-owned companies involved in building and repairing these cables. This is the case for Huawei Marine, which has built or repaired nearly one quarter of all submarine cables. Cable builder companies, especially those controlled by a government, can be coerced to integrate backdoors into the equipment before deployment, enabling to hack into the cable without first having to tap into it underwater or on land (Sherman, 2023).

In the case of Russia, the concerns do not derive from its investments but rather its military activity near submarine cables (Sherman, 2023). Especially this year, multiple signs were detected by the United States. Additionally, Russia is seemingly expanding its undersea capabilities among the Russian navy and the Main Directorate for Deep Sea Research (GUGI) (Cwalina, 2024). GUGI operates specialized submarines, currently including X-Ray, Kashalot and Paltus which can function at extreme depths. The deeper the location of the cable cut, the more difficult and longer the repair process will be (Kaushal, 2023). It is believed that a deliberate attack on the underwater infrastructure could soon become a tool in Russia’s hybrid warfare against the West (Cwalina, 2024).

How are submarine cables protected?

There are various security measures that are employed to protect the submarine cables from damage or sabotage and strengthen their resilience. Physical protection measures include burying the cable in the ocean floor or adding layers of coatings and armouring, enhancing their robustness against sabotage, accidental damage from fishing nets and ship anchors and natural disasters. To safeguard against cyber-attacks, all network infrastructure, including cable landing stations and equipment should be regularly updated. Furthermore, intrusion detection systems, robust encryption protocols and authentication mechanisms should be implemented. Regular maintenance is important to detect new vulnerabilities, cable faults or tampering signs, which can prevent more severe damage in the future (Pandey & Bhushan, 2023).

The resilience of the submarine cable network must be strengthened as well. Resilience means that even if a cable is damaged or services are disrupted, contingency plans are in place that will ensure timely repair, continuation of services or in case of a disruption the resuming of services as soon as possible. This can be achieved by deploying real-time surveillance systems that will alert immediately in face of a physical and cyber threats (Pandey & Bhushan, 2023). In 2021, the UK government announced the new Multi Role Ocean Surveillance ship (MROSS), equipped with autonomous underwater drones and advanced sensors for monitoring capabilities. It was planned to come into service by the end of this year (UK Ministry of Defence, 2021). Each cable route should have a backup as well as alternative landing stations, ensuring that communications will not be disrupted despite damage (Pandey & Bhushan, 2023). While cable projects are mainly privately managed, it is the governments’ responsibility to conduct national risk assessments. For instance, the US interagency group ‘Team Telecom’ reviews the potential national security consequences linked to all submarine cables landing on American soil. Moreover, governments should encourage private companies to follow voluntary guidelines such as those by the International Cable Protection Committee or define mandatory requirements. The resilience of submarine cables is also an international concern, implying the necessity of international action. NATO allies should share more intelligence regarding their respective cable projects, their national protection measures and their threat analyses (Morcos & Wall, 2021).

Another important aspect contributing to the resilience of underwater infrastructure are repair capabilities. The repair of a damaged cable can cost between $1-3 million due to requiring a specialized cable repair ship and a highly trained crew (Runde et al., 2024). Typically, operators have cable repair resources that are ready to respond within 24 hours of a failure. Despite the fast response, the repair process can take months because the damaged optical fiber ends have to be located, pulled to the surface and be respliced, meaning to be joined back together (Saffo, 2013). In 2021, the United States implemented the Cable Security Fleet (CSF), operated by SubCom, one of the largest underwater fiber optic cable developers, and consisting of the CS Dependable and the CS Decisive. These ships have to be available for laying, maintaining and repairing submarine cables at all times, particularly during a national emergency or war (Runde et al., 2024). Furthermore, regular exercises are advised to determine points of improvement during the repair process, which can be done on a unilateral or multilateral level (Morcos & Wall, 2021).

Conclusion

The submarine cable network is extremely critical for the functioning of our modern society. It presents an additional target that can be attacked during a conflict or war, of which the consequences could further change the course of the war. While various security measures are already implemented, threat actors continuously find new ways to target submarine cables and achieve their malicious objective. However, the accidental and natural damage to submarine cables should not be ignored either, since it makes up the majority of annual damage. With our lives becoming more and more depended on submarine cables, it is important to continously improve their security measures.

Reference list

- Burnett, D. R. & Berdan, K. (2024). To Secure Undersea Cables, Take Lessons from the British Empire’s All-Red Line. Proceedings, 150(7). https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2024/july/secure-undersea-cables-take-lessons-british-empires-all-red-line

- Corera, G. (2017a, December 15). How Britain pioneered cable-cutting in World War One. Retrieved October 8, 2024, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-42367551

- Corera, G. (2017b, January 17). Why was the Zimmermann Telegram so important? Retrieved October 8, 2024, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-38581861

- Cwalina, A. (2024, September 12). Concerns grow over possible Russian sabotage of undersea cables. Retrieved October 8, 2024, from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/concerns-grow-over-possible-russian-sabotage-of-undersea-cables/

- Kaushal, S. (2023, May 25). Stalking the Seabed: How Russia Targets Critical Undersea Infrastructure. Retrieved October 8, 2024, from https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/stalking-seabed-how-russia-targets-critical-undersea-infrastructure

- Miani, L. (2020). Strategic Geography of the Internet. Retrieved October 8, 2024, from https://affiliate-network.co/2020/09/strategic-geography-internet/

- Pandey, S.K. & Bhushan, A. (2023). Submarine Cables: Issues of Maritime Security, Jurisdiction, and Legalities. European Journal of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, 1(4),117-132. https://doi.org/10.59324/ejtas.2023

- Runde, D. S., Murphy, E. L. & Bryja, T. (2024, August 16). Safeguarding Subsea Cables: Protecting Cyber Infrastructure amid Great Power Competition. Retrieved October 8, 2024, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/safeguarding-subsea-cables-protecting-cyber-infrastructure-amid-great-power-competition

- Saffo, P. (2013, April 4). Disrupting Undersea Cables: Cyberspace’s Hidden Vulnerability. Retrieved October 8, 2024, from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/disrupting-undersea-cables-cyberspaces-hidden-vulnerability/

- Sherman, J. (2021, September 12). Cyber defense across the ocean floor: The geopolitics of submarine cable security. Retrieved October 8, 2024, from https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/cyber-defense-across-the-ocean-floor-the-geopolitics-of-submarine-cable-security/

- Sherman, J. (2023). Cybersecurity under the Ocean. Hoover Institution. https://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/Sherman_CybersecurityUnderOcean_web-rev.pdf

- UK Ministry of Defence. (2021). New Royal Navy Surveillance Ship to protect the UK’s critical underwater infrastructure [Press release]. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-royal-navy-surveillance-ship-to-protect-the-uks-critical-underwater-infrastructure

- Wall, C. & Morcos, P. (2021, June 11). Invisible and Vital: Undersea Cables and Transatlantic Security. Retrieved October 8, 2024, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/invisible-and-vital-undersea-cables-and-transatlantic-security

- Winseck, D. (2017). The Geopolitical Economy of the Global Internet Infrastructure. Journal of Information Policy, 7, 228-267. https://doi.org/10.5325/jinfopoli.7.2017.0228

While we are transparent about all sources used in this article and double-checked all the given information, we make no claims about its completeness, accuracy or reliability. If you notice a mistake or misleading phrasing, please contact centuria-sa@hhs.nl .

This article also contains links to other third-party websites, which have only been placed for the convenience of the reader and do not imply endorsement of contents of said third-party websites.

Leave a comment