By Larisa Kasler

Introduction

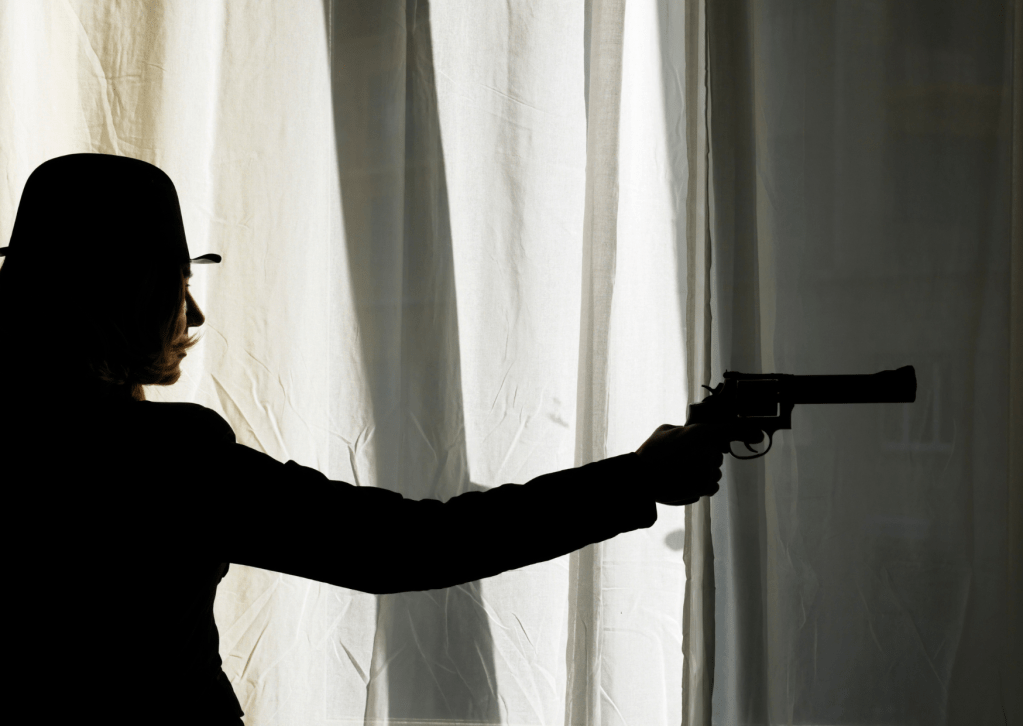

Being a world of shadowy figures which shaped the course of history behind the scenes, espionage has mostly been viewed as a domain dominated by men. From James Bond to Mission: Impossible, espionage has long been shaped as a daring, exciting, and thrilling career, in which intelligent men exchange coded messages, jump out of helicopters, and engage in high-speed chases and brutal fights. However, this perception overlooks the significant and often underappreciated role of women in intelligence. From ancient times to modern cyber warfare, women have served as couriers, analysts, operatives, spies, and even military strategists, using their social underestimation to their advantage.

Despite their great contributions, women in intelligence have faced systemic barriers and were limited by patriarchal constraints. According to Amy J. Martin’s research on the evolution of women in intelligence (mainly focused on the United States), women working in the CIA were receiving proportionately fewer awards, while also being stunted from moving into senior positions (Martin, 2015). Even those who excelled in their roles struggled to gain leadership positions. Stella Rimington, the first female Director-General of MI5 in 1992, faced institutional resistance throughout her career. Intelligence agencies were reluctant to place women in command, assuming they lacked the temperament for leadership (Fry, 2023). While sexual harassment against women was tolerated, they had to also battle the assumption that being underestimated made their job easier, rather than recognizing it as an obstacle. Yet, the modern landscape is changing. Women now hold leadership in agencies such as the CIA, MI6, and the Mossad, contributing to espionage and intelligence gathering.

This article explores the historic role of women in intelligence, analyzing the challenges, contributions, and evolving roles in the intelligence community. By shedding light on their achievements, we not only rewrite the patriarchal narrative of intelligence history but also acknowledge the strength and ingenuity of the women who partook in the ‘world of shadows’.

A Brief History

The history of female spies is as old as espionage itself. Over the centuries there have been colorful, clever, and dedicated women, all engaged in gathering secret information. In ancient times, women used their societal roles to overhear and pass on intelligence and often served as informants, couriers, and intermediaries. Their societal roles allowed them to move undetected, making them the ideal spies. One of the earliest known female spies is Rahab, a woman mentioned in the Book of Joshua, who hid Israelite spies in Jericho and provided them with intelligence that led to the city’s conquest (New International Version Bible, 1978/2011, Josh. 2:2). Similarly, during the Roman Empire, Fulvia, the wife of senator Mark Antony, allegedly intercepted messages and influenced political decisions through her strategic alliances (Murdarasi, 2022). As intelligence gathering became more structured, so did the role of women within it. The American Revolution, the Civil War, and both World Wars saw an increasing reliance on female spies who could operate undetected, eavesdropping on conversations, and delivering crucial information. While countless women contributed to espionage efforts, a few stood out for their daring missions and impact on history. Some of the most remarkable figures in the history of intelligence include Agent 355, Harriet Tubman, Mata Hari, and Virginia Hall, each of whom operated in different circumstances.

1. Agent 355

The American Revolution (1775–1783) was not just a war fought on battlefields – it was a war of secret communication and espionage. The British Empire, the world’s most powerful military force at the time, faced the 13 American colonies that sought independence. The colonies had little formal military power, so intelligence played a crucial role in outmaneuvering the British. One of the most important spy networks during the war was the Culper Spy Ring, organized by George Washington and his intelligence chief Benjamin Tallmadge. This network gathered intelligence from British-occupied New York and relayed it to Washington, often using ciphers, invisible ink, and dead drops. Within this ring was Agent 355, one of the earliest known female spies in American history (Bleyer, 2023).

Agent 355’s most significant contribution was her role in uncovering the treason of Benedict Arnold, a high-ranking American general who plotted to hand over West Point, an important military fort, to the British. Arnold had been a celebrated hero in early battles of the revolution but grew resentful of what he saw as unfair treatment from the Congress and his superiors. Believing he was undervalued and financially unstable, he secretly negotiated with the British to surrender West Point in exchange for money and a command position in the British Army. His plan was exposed when Major John André, his British contact, was captured carrying incriminating documents. Many historians believe that Agent 355 played a role in uncovering this plan, as she had access to British officers and their Loyalist allies in New York City. Her intelligence helped lead to André’s execution and forced Arnold to flee to the British side, where he lived in disgrace for the rest of his life. Agent 355’s true identity remains unknown, but some believe she was captured and died aboard a British prison ship. Others theorize that she continued her work, vanishing into history after the war. Regardless of her fate, she demonstrated how women, even in an era when they were dismissed as passive participants, played an important role in intelligence (Bleyer, 2021).

2. Harriet Tubman

By the time the American Civil War (1861–1865) began, the United States was deeply divided over the issue of slavery. The Southern states, forming the Confederacy, seceded from the Union to protect their economy, which relied on enslaved labor. The Union Army, led by President Abraham Lincoln, fought to preserve the nation and later to abolish slavery altogether (Winkler, 2010). Harriet Tubman was already famous before the war as the most successful ‘conductor’ of the Underground Railroad, a network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom in the North. She was capable of avoiding capture, and organizing escape plans for enslaved African Americans, which made her a natural candidate for espionage. She was recruited by the Union Army as a scout and spy, using her deep knowledge of the South to infiltrate Confederate territory (Winkler, 2010). Her most remarkable intelligence mission was the Combahee River Raid in 1863, a Union operation in South Carolina. Tubman and a team of Union scouts gathered intelligence on Confederate defenses, supply routes, and locations of enslaved populations. Based on her intelligence, Union gunboats moved up the river, evading Confederate mines and traps. Once onshore, Tubman personally led the Union soldiers in burning plantations, destroying Confederate supply lines, and freeing more than 700 enslaved men, women, and children. This raid was a significant blow to the Confederacy, as it not only weakened their labor force but also proved that formerly enslaved people could take up arms against the South (Winkler, 2010).

3. Mata Hari

The First World War (1914–1918) was a brutal conflict between the Allied Powers (including France, Britain, and Russia) and the Central Powers (led by Germany and Austria-Hungary). Unlike previous wars, World War I relied heavily on trench warfare, aerial reconnaissance, and intelligence gathering. Mata Hari, born Margaretha Geertruida Zelle, was a Dutch woman who rose to fame as an exotic dancer and courtesan in early 20th-century Europe. She crafted a mysterious identity, claiming to be an Indonesian princess trained in sacred temple dances. Her performances attracted high-ranking military officials, diplomats, and politicians, giving her access to sensitive military conversations. During the war, she was approached by both French and German intelligence agencies, though her exact role remains controversial. Some claim she worked as a double agent, while others believe she was merely a scapegoat for French military failures. She accepted payments from both sides, leading French authorities to suspect her of treason. In 1917, French intelligence intercepted coded messages referring to a spy named H-21, allegedly Mata Hari. She was arrested, tried for espionage, and sentenced to death by firing squad. Her execution was one of the most sensationalized spy cases in history, the opinions diverging whether she was a true spy or an innocent woman caught in the paranoia of war (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2024).

4. Virginia Hall

During World War II (1939–1945), espionage became a battlefield of its own. The Gestapo, Nazi Germany’s secret police, ruthlessly hunted down spies who worked with the Allied forces. Among their most-wanted enemies was an American woman named Virginia Hall, who worked for the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and later the CIA. Hall’s story stands out not just because of her espionage skills, but also because she operated with a prosthetic leg, having lost her left leg in a hunting accident. Despite this, she infiltrated Nazi-occupied France, working with the French Resistance to organize sabotage missions, assassinate German officers, and coordinate arms shipments. Her ability to blend in was unmatched. When the Nazis learned of her presence and issued orders for her capture, she escaped on foot across the Pyrenees Mountains into Spain – an impressive and painful journey, given her wooden leg. She later returned to France under a new identity and continued her work until the war ended. The Gestapo considered her “the most dangerous of all Allied spies (Friddell, 2025), yet she was never caught. After the war, she joined the CIA, becoming one of the first women to work in American intelligence (Purnell, 2019).

Techniques and Challenges in Espionage

Women in intelligence have been forced to adapt, often using society’s underestimation of them as a weapon. While men in espionage relied on brute force or open authority, female spies developed unique techniques, exploiting gender stereotypes while mastering the art of deception. But their success came at a cost, as intelligence agencies often failed to acknowledge their contributions, relegating them to administrative roles even when they had proven themselves in the field (Fry, 2023).

One of the greatest tools female spies had was the assumption that women were not spies. Historically, women were viewed as harmless, incapable of understanding politics or military strategy, making them perfect for intelligence work. This perception allowed female agents to move undetected, gathering secrets and passing information without gaining suspicion. While the idea of female spies using seduction to gain information has been sensationalized, there is truth to the notion that women in espionage manipulated relationships to extract secrets. However, this was far more than simple flirting. It required careful psychological games such as exploiting male egos and emotionally manipulating them. In the Cold War, for instance, intelligence agencies like the KGB, MI6, and the CIA trained women in said psychological manipulation rather than relying solely on seduction (Fry, 2023). Female agents were taught how to gain confidants by building trust and subtly extract classified information from their targets. Some were recruited to act as honey traps (using seduction, romance, and emotional manipulation), but others worked as handlers, persuading male spies to defect or betray their countries.

Female codebreakers and deep-cover operatives

However, not all espionage took place in the field. Many of the most crucial intelligence victories came not from undercover agents but from those working behind the scenes to break enemy codes and intercept communications. Women played a significant role in this invisible war. During World War II, the British government recruited thousands of women to work as cryptographers at Bletchley Park, the secret intelligence center responsible for breaking Nazi codes. Joan Clarke, one of the top codebreakers, worked alongside Alan Turing in deciphering the Enigma code, which allowed the Allies to intercept German military communications. Her work, though largely unrecognized at the time, contributed to shortening the war. Similarly, in the United States, women working at the Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) helped crack the Japanese Purple cipher, giving the U.S. government a strategic advantage in the Pacific theatre. These women were often dismissed as simple clerks or assistants, yet their intelligence work was just as decisive as that of the soldiers fighting on the front lines (Fry, 2023).

As deep-cover operatives, several women accepted risky tasks by infiltrating resistance groups and areas of conflict. Women were able to blend in more easily than male spies, who were frequently discovered and killed. The first female radio operator deployed into occupied France was Noor Inayat Khan, a British-Indian spy for the Special Operations Executive (SOE). The Gestapo actively attempted to intercept wireless operators’ signals, making them one of the most sought-after persons in Nazi-controlled Europe. Noor refused to leave her station until she was finally apprehended and sentenced to death, despite the fact that her whole network had been infiltrated (Fry, 2023).

Conclusion

All in all, women have always been important in espionage, using their skills, determination, and ability to work around society’s expectations to succeed. They worked as codebreakers, undercover agents, and military planners, helping to win wars and protect national security. Today, women continue to play a big role in intelligence, taking on leadership positions and changing old ideas about what a spy should be. As technology and global security become more advanced, their role in intelligence will only grow—showing that the best spies are often the ones no one suspects.

Reference list

Bleyer, B. (2021). George Washington’s Long Island: A History and Tour Guide. Arcadia Publishing.

Fry, H. (2023). Women in Intelligence. Yale University Press.

Friddell, C. (2025). The mysterious Virginia Hall: World War II’s Most Dangerous Spy. Astra Publishing House.

Murdarasi, K. (2019, April 4). Fulvia: The Roman woman who would be king. History Today 69(4). https://www.historytoday.com/archive/history-matters/fulvia-roman-woman-who-would-be-king

Martin, A. (2015). America’s evolution of women and their roles in the intelligence community. Journal of Strategic Security, 8(3Suppl), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.8.3s.1479

New International Version Bible. (2011). Holy Bible. (Original work published 1978). Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Joshua+2&version=NIV

Purnell, S. (2019). A woman of no importance: The Untold Story of Virginia Hall, WWII’s Most Dangerous Spy. Hachette UK.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024, December 17). Mata Hari | Biography, Spy, Photos, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mata-Hari-Dutch-dancer-and-spy

Winkler, H. D. (2010). Stealing Secrets: How a few daring women deceived generals, impacted battles, and altered the course of the Civil War. Cumberland House.

While we are transparent about all sources used in this article and double-checked all the given information, we make no claims about its completeness, accuracy or reliability. If you notice a mistake or misleading phrasing, please contact centuria-sa@hhs.nl .

Leave a comment